World AIDS Day 2006. Well, we pulled it off successfully, sort of. The boda-bodas got to race, we registered 35 people to participate in an HIV workshop (pending funding), they got awesome prizes, free food and water, and bragging rights. In reality, we took a bunch of shortcuts so that to the public it looked organized. To give you a little sampling of the bigger frustration, the district coordinating body didn’t announce the venue until four days before the event. FOUR DAYS. My co-workers weren’t kidding about last minute “planning” skills of local leaders, although they left out the part about the finger-pointing and refusal to accept responsibility for failure...and curiously enough, the simultaneous eagerness to take credit for someone else’s work.

Eric, Neetha and Adrienne came to my site to help out with race-day logisitics. We passed out World AIDS Day stickers, caps and flags, water, biscuits and bread; numbered the racers, registered last-minute entrants, and motored through town as part of the parade. Students from a nearby university, which was hosting the main event, marched with banners and flags, and wore yellow t-shirts that said, “I Care To Know My HIV Status. Do You?” A matatu tout ran up to us as we were riding in our vehicle and said, “Let me ask you just one question. Those students marching, do they have AIDS? Because some of them are so beautiful, I hope not.”

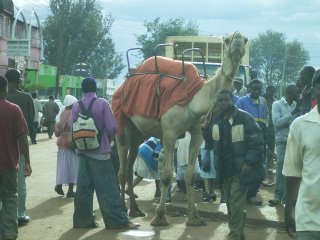

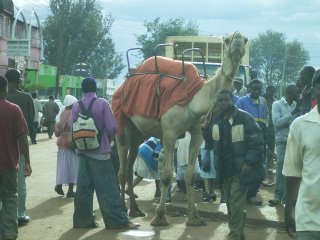

Adrienne and I had ridden the route on our Peace Corps-issue mountain bikes a few days earlier to mark checkpoints and get a sense for how long the race would take. We stopped several times for pouring rain, food and water, and it took us six hours to complete the 54 km route. The boda-bodas completed the route in just over two hours on their clunky fake-Chinese bikes like the ones you see to the left.

There were the usual speeches, poems and skits, as well as a prize-giving ceremony for the racers, who had stuffed themselves full of bread, biscuits and glucose powder. That stuff is fascinating. Glucose is given to people when they’re sick, to kids as a snack during school, and as sustenance during strenuous activity. The best part is that you just pour a small mound into the palm of your hand and lick it clean, so after awhile all the boda-bodas had white powder all over their mouths and noses. It did NOT resemble a coke-snorting convention. Hehe.

Thanksgiving Day 2006. It is a Peace Corps tradition to match volunteers to American ex-pat host families for Thanksgiving each year. I spent Thanksgiving with a couple who works for a U.S. government agency in Nairobi, and allow me to make a note to myself for future reference: Foreign Service Officer = cushy lifestyle. The husband served in the Peace Corps several decades ago, and the wife has lived and worked all over the world. They invited me and two other volunteers into their cavernous home in the suburbs of Nairobi. It’s a 100 percent American house, with Kenyan flare – two giant, friendly dogs, a giant refrigerator, a giant washer and dryer, giant fluffy towels that smell like dryer sheets, flushing toilets, hot water, bathtubs, housekeeper and housekeeper quarters, satellite TV, soon-to-arrive wireless internet, landscaped gardens, two series of gates and guards, U.S. government-issue Land Rover, elaborate security system, marble fireplace, wood floors…oh, God, stop me now. Anyway, an oasis of American comfort (uh, luxury) in a developing country, and I didn’t even feel guilty being there. I’ve definitely been in the village too long. Thank God I’m going home to get a good dose of vulgar American consumerism and gluttony to make me appreciate the simplicity of Kenyan village life.

But I digress. Thanksgiving dinner was the works: a 20-lb turkey, mushroom gravy (real mushrooms!), autumn vegetables, salad (oh loverly raw vegetables), another turkey breast marinated in beer, butternut squash soup, pie, pie, pie…and they are wine collectors so for the first time in Kenya I actually drank good wine.

It made my day. It made my week and month, too. It was a vacation to a familiar place I’d never been to before, with familiar people I’d never met before. It’s pretty amazing how in Kenya you can put a bunch of American strangers together who really don’t have that much in common, and we easily find so much in common. It’s true a lot of it comes from a consumer culture we share (“Cranberry sauce. Where are we going to find cranberry sauce?”) But a lot of it also comes from traditions we share, and from a very specific set of values that we’re not aware we share with each other until we live in a place like Kenya that is so different, and baffling, and challenging to all the beliefs we assumed were pretty universal. They’re not. We can’t understand why they’re not, because they seem so obviously right, and true, and best. But we can share that inability to understand with other American ex-pats, and it’s comforting…it’s a realization that even 20,000 (50,000?) miles from home, we’re not alone.